We have a problem with Eduhelmin, a drug recently approved to treat Alzheimer’s. Although it can eliminate part of the amyloid that forms the brain plaques characteristic of this disease, most of the drug is wasted as it moves across a barrier: the blood-brain barrier, which protects the brain from toxins and infections. Protects, but also prevents, the penetration of many drugs.

The researchers wondered whether they could improve the disappointing results if they tried something different: opening the blood-brain barrier for a short time while giving the drug. Their experimental method was to use well-directed ultrasound pulses with tiny gas bubbles to open the barrier without destroying it.

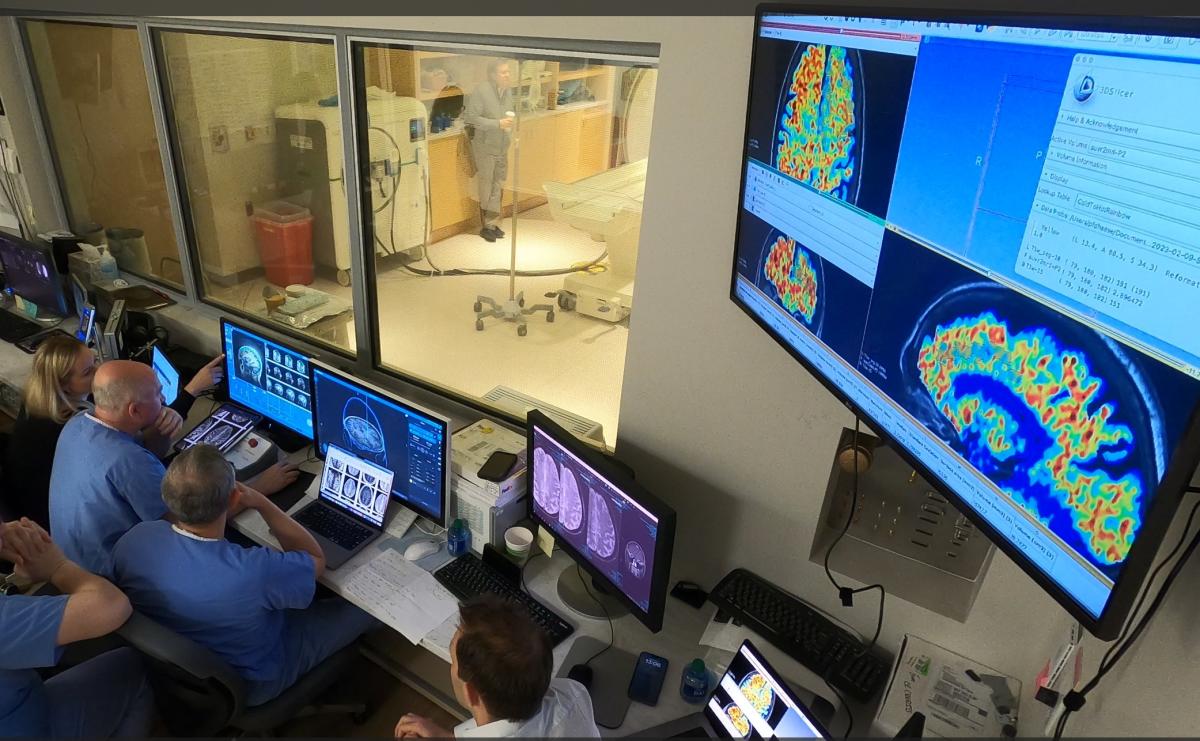

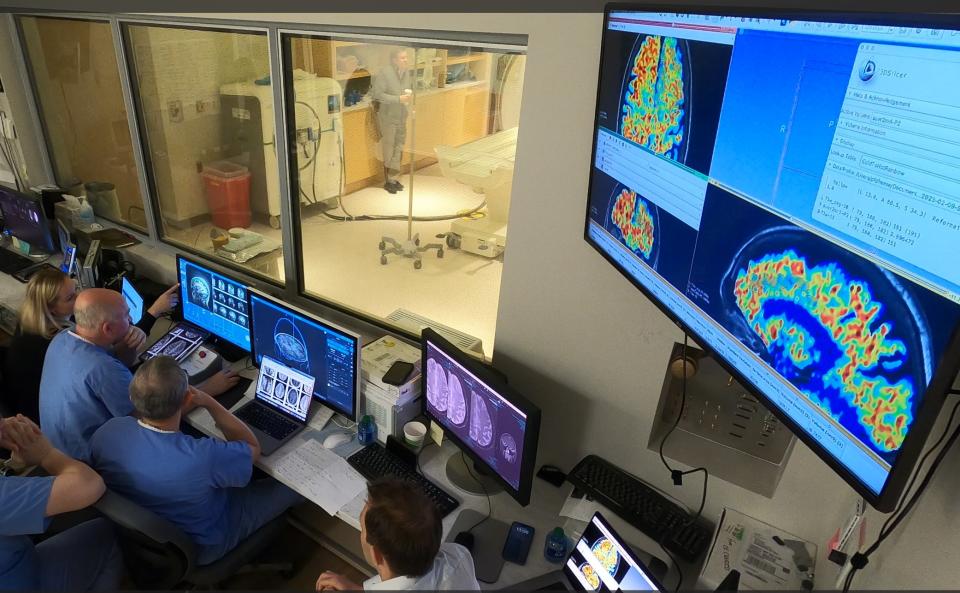

Researchers at West Virginia University’s Rockefeller Neuroscience Institute recently reported their results in The New England Journal of Medicine. When the barrier was opened, 32 percent or more of the plaque dissolved, said Ali Rezaei, a neurosurgeon at the institute who led the study. The group didn’t measure the amount of antibody entering (that would require labeling the drug with radioactivity), Rezai said, but in animal studies, opening the barrier allowed five to eight times more antibodies to enter the brain. Got permission to do it.

In its initial phase, the experiment, which was conducted with only three patients with mild Alzheimer’s, was funded by this university and the Harry T. Mangurian, Jr. Foundation.

This was a preliminary safety study – the first phase of research – and was not designed to measure clinical outcomes.

But when the results were presented at a recent meeting, “we were blown away,” said Michael Weiner, an Alzheimer’s disease researcher at the University of California, San Francisco, who was not involved in the study.

The researchers noted that this was an innovative, but complex approach to Walter Koroshetz’s problem., Director of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, brain diseases are considered one of the biggest challenges in treating: How do drugs get into the brain?

Some antibodies, such as the Alzheimer’s drug aducanumab, which Biogen sells as Aduhelminth, are prohibitively expensive; Its selling price is $28,000 for one year’s treatment. According to Koroshetz, one reason for this high price is that only one percent of antibodies injected into the bloodstream manage to cross the blood-brain barrier.

However, it took more than a decade to find a safe way to open that barrier. Researchers knew how the barrier worked, but because of its role in protecting the brain, opening it without damaging it meant keeping it open only for very short periods of time. It is a very delicate part of the circulatory system and is not what many people imagine from its name.

“A lot of people think of it as a thing that wraps around the head,” said Alexandra Golby, a professor of neurosurgery and radiology at Harvard Medical School, “a kind of turban for the brain.”

Instead, the blockage is found at the ends of several vital blood vessels that supply the brain. When they reach the head, the vessels branch and divide until their ends become narrow capillaries with extremely tight walls. This barrier does not allow large molecules to pass, but allows small molecules such as glucose and oxygen to pass through.

The challenge was to open those walls without breaking the capillaries.

Two elements emerged in the solution. First, patients are injected with tiny microscopic bubbles of perfluorocarbon gas. The size of the bubbles ranges from 1.1 to 3.3 microns (a micron measures one thousandth of a millimeter). Low-frequency ultrasound pulses are then directed to the area of the brain to be treated. Ultrasound pulses create waves in the fluid of the blood vessels causing microscopic bubbles to rapidly expand and contract with the waves. This opens the blood vessels without causing damage and provides access to the brain.

According to Golby, microbubbles are routinely used in ultrasound imaging studies of the heart and liver because they light up and reveal blood flow. Both the kidneys and liver filter them from the body.

“We’ve used them safely for 20 years,” Golby said.

For the experiment described in this new paper, researchers used ultrasound on one side of the brain, but not the other, and then scanned the brain to verify the results.

Although the targeted ultrasound method was successful as an experiment, not everything was so promising. The device was designed to deliver ultrasound to a small, specific area, but in cases of Alzheimer’s, amyloid-containing plaques occur throughout the brain.

“If we want to get amyloid out of the brain, we have to go in with a paintbrush instead of a pencil,” he told Koroshetz.

Researchers intentionally target areas of the brain related to memory and reasoning, but it is not yet known whether the treatment improves outcomes. A larger study will be needed to find out.

The Alzheimer’s study is one of many that involve overcoming barriers to delivering drugs to patients with a variety of brain diseases.

This is all in the early stages and so far everything shows that this method works; Medicines that were otherwise unable to penetrate have now managed to do so.

A group led by neurosurgeon Nir Lipsman and colleagues at the Sunnybrook Research Institute at the University of Toronto opened the door to delivering chemotherapy drugs into the brains of four patients with breast cancer that had spread to the brain. The researchers reported that the concentration of the drug, trastuzumab, increased fourfold.

That work was funded by the Focused Ultrasound Foundation and sponsored by Insitec, which makes the ultrasound machines used.

Lipsman and his colleagues have already treated seven breast cancer patients and are expanding the study. They are also conducting preliminary studies on a variety of brain diseases, including cancer, Parkinson’s, and Lou Gehrig’s disease, or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

Golby and his colleagues have used this approach to treat patients with glioblastoma, a deadly type of brain cancer.

c.2024 New York Times Company

(Tags to translate)West Virginia University(T)Blood-brain barrier(T)Alzheimer’s disease(T)University of California